Labor Day is a U.S. national holiday held the first Monday every September. Unlike most U.S. holidays, it is a strange celebration without rituals, except for shopping and barbecuing. For most people it simply marks the last weekend of summer and the start of the school year.

The holiday’s founders in the late 1800s envisioned something very different from what the day has become. The founders were looking for two things: a means of unifying union workers and a reduction in work time.

History of Labor Day

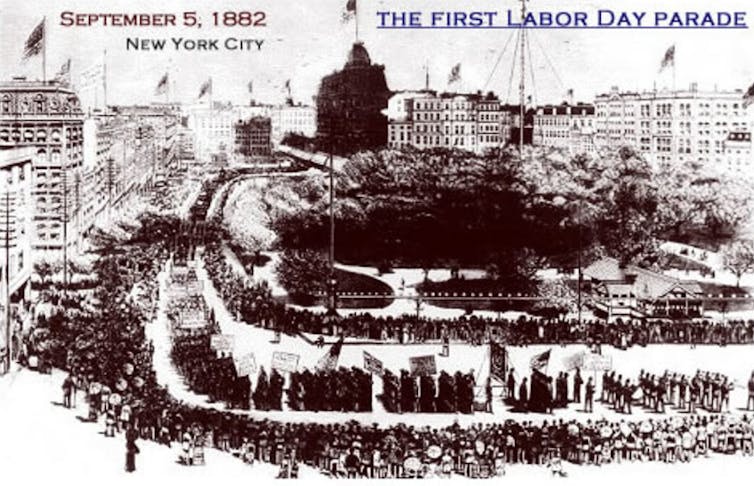

The first Labor Day occurred in 1882 in New York City under the direction of that city’s Central Labor Union.

In the 1800s, unions covered only a small fraction of workers and were balkanized and relatively weak. The goal of organizations like the Central Labor Union and more modern-day counterparts like the AFL-CIO was to bring many small unions together to achieve a critical mass and power. The organizers of the first Labor Day were interested in creating an event that brought different types of workers together to meet each other and recognize their common interests.

However, the organizers had a large problem: No government or company recognized the first Monday in September as a day off work. The issue was solved temporarily by declaring a one-day strike in the city. All striking workers were expected to march in a parade and then eat and drink at a giant picnic afterwards.

The New York Tribune’s reporter covering the event felt the entire day was like one long political barbecue, with “rather dull speeches.”

Why was Labor Day invented?

Labor Day came about because workers felt they were spending too many hours and days on the job.

In the 1830s, manufacturing workers were putting in 70-hour weeks on average. Sixty years later, in 1890, hours of work had dropped, although the average manufacturing worker still toiled in a factory 60 hours a week.

These long working hours caused many union organizers to focus on winning a shorter eight-hour work day. They also focused on getting workers more days off, such as the Labor Day holiday, and reducing the workweek to just six days.

These early organizers clearly won since the most recent data show that the average person working in manufacturing is employed for a bit over 40 hours a week and most people work only five days a week.

Surprisingly, many politicians and business owners were actually in favor of giving workers more time off. That’s because workers who had no free time were not able to spend their wages on traveling, entertainment or dining out.

As the U.S. economy expanded beyond farming and basic manufacturing in the late 1800s and early 1900s, it became important for businesses to find consumers interested in buying the products and services being produced in ever greater amounts. Shortening the work week was one way of turning the working class into the consuming class.

Common misconceptions

The common misconception is that since Labor Day is a national holiday, everyone gets the day off. Nothing could be further from the truth.

While the first Labor Day was created by striking, the idea of a special holiday for workers was easy for politicians to support. It was easy because proclaiming a holiday, like Mother’s Day, costs legislators nothing and benefits them by currying favor with voters. In 1887, Oregon, Colorado, Massachusetts, New York and New Jersey all declared a special legal holiday in September to celebrate workers.

Within 12 years, half the states in the country recognized Labor Day as a holiday. It became a national holiday in June 1894 when President Grover Cleveland signed the Labor Day bill into law. While most people interpreted this as recognizing the day as a national vacation, Congress’ proclamation covers only federal employees. It is up to each state to declare its own legal holidays.

Moreover, proclaiming any day an official holiday means little, as an official holiday does not require private employers and even some government agencies to give their workers the day off. Many stores are open on Labor Day. Essential government services in protection and transportation continue to function, and even less essential programs like national parks are open. Because not everyone is given time off on Labor Day, union workers as recently as the 1930s were being urged to stage one-day strikes if their employer refused to give them the day off.

In the president’s annual Labor Day declaration last year, Obama encouraged Americans “to observe this day with appropriate programs, ceremonies and activities that honor the contributions and resilience of working Americans.”

The proclamation, however, does not officially declare that anyone gets time off.

Controversy: Militants and founders

Today most people in the U.S. think of Labor Day as a noncontroversial holiday.

There is no family drama like at Thanksgiving, no religious issues like at Christmas. However, 100 years ago there was controversy.

The first controversy that people fought over was how militant workers should act on a day designed to honor workers. Communist, Marxist and socialist members of the trade union movement supported May 1 as an international day of demonstrations, street protests and even violence, which continues even today.

More moderate trade union members, however, advocated for a September Labor Day of parades and picnics. In the U.S., picnics, instead of street protests, won the day.

There is also dispute over who suggested the idea. The earliest history from the mid-1930s credits Peter J. McGuire, who founded the New York City Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, in 1881 with suggesting a date that would fall “nearly midway between the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving” that “would publicly show the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations.”

Later scholarship from the early 1970s makes an excellent case that Matthew Maguire, a representative from the Machinists Union, actually was the founder of Labor Day. However, because Matthew Maguire was seen as too radical, the more moderate Peter McGuire was given the credit.

Who actually came up with the idea will likely never be known, but you can vote online here to express your view.

Have we lost the spirit of Labor Day?

Today Labor Day is no longer about trade unionists marching down the street with banners and their tools of trade. Instead, it is a confused holiday with no associated rituals.

The original holiday was meant to handle a problem of long working hours and no time off. Although the battle over these issues would seem to have been won long ago, this issue is starting to come back with a vengeance, not for manufacturing workers but for highly skilled white-collar workers, many of whom are constantly connected to work.

If you work all the time and never really take a vacation, start a new ritual that honors the original spirit of Labor Day. Give yourself the day off. Don’t go in to work. Shut off your phone, computer and other electronic devices connecting you to your daily grind. Then go to a barbecue, like the original participants did over a century ago, and celebrate having at least one day off from work during the year!![]()

Jay L. Zagorsky, Senior Lecturer, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.